If you mention edible electronics to someone, the first question will probably be – How can you eat electronics anyway? The answer is yes, you can, if you produce electronics from edible materials. So, imagine instead of a gastroscopic probe you get to eat a sensor made from peas and apples that can measure biomarkers from the mouth to the stomach. Such an edible sensor was developed by the team from the Faculty of Technical Sciences in Novi Sad, together with their partners on GREENELIT project.

This is one of five major projects coordinated by Goran Stojanović, a full professor at FTN and leader of the Group for nano and flexible electronics. According to him, the projects he is engaged in are his life, and the number of successful European projects he has worked on is impressive; so far, there are over 50.

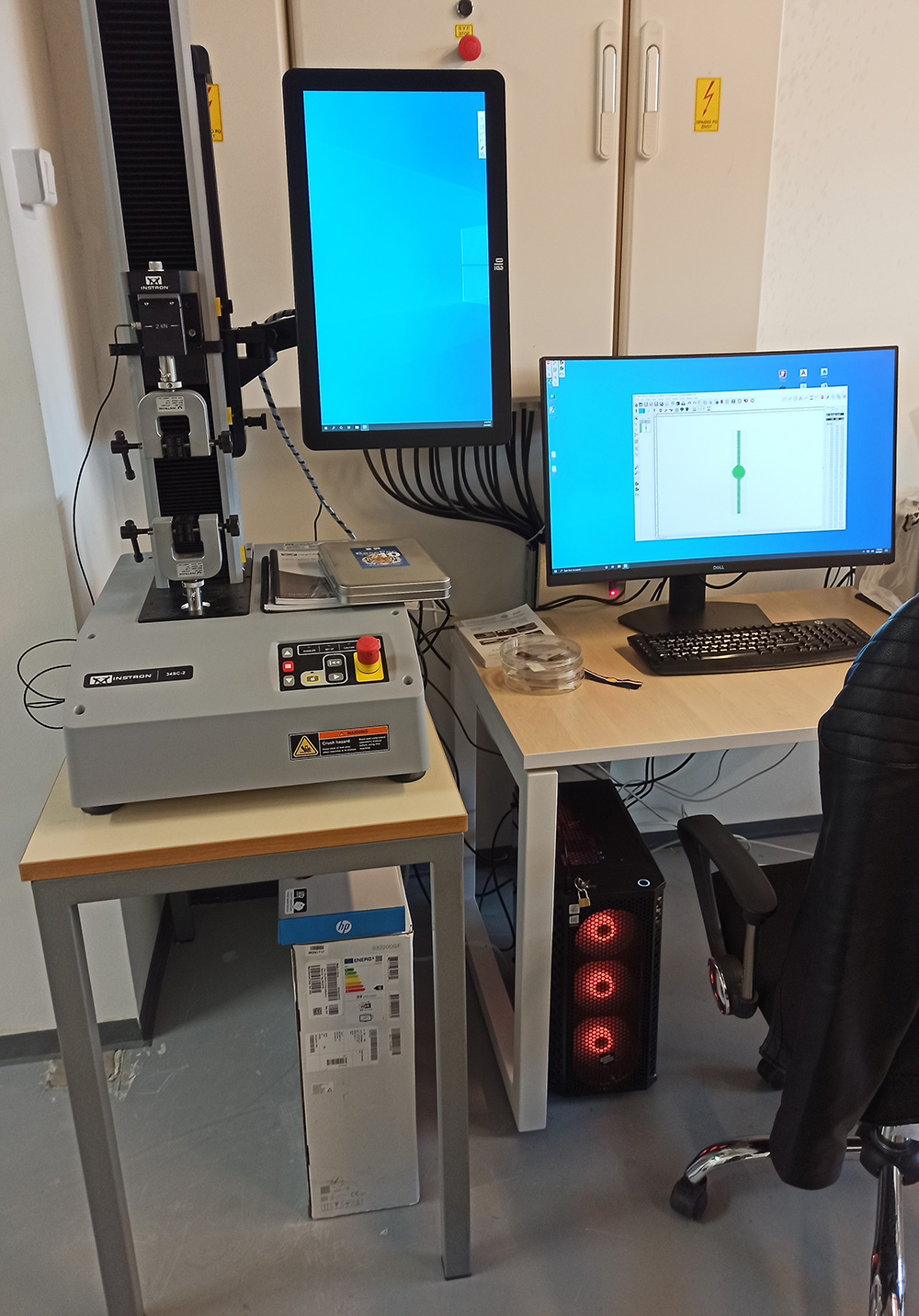

“I dedicated the past 15 years of my life to pointing to the importance of writing competitive science projects. All those projects were used to permanently change the image of Serbia in Europe and among students. Our labs, our knowledge, and equipment are on par with leading European centres in the area of green, flexible, or textile electronics. They see us as a partner they want to work with. And that’s a strategic path of our development. And that is why we should try hard to get funds that are at our disposal,” Stojanović says.

“I dedicated the past 15 years of my life to pointing to the importance of writing competitive science projects. All those projects were used to permanently change the image of Serbia in Europe and among students. Our labs, our knowledge, and equipment are on par with leading European centres in the area of green, flexible, or textile electronics. They see us as a partner they want to work with. And that’s a strategic path of our development. And that is why we should try hard to get funds that are at our disposal,” Stojanović says.

And he did snatch 20 of them and used them to secure 7.4 million euros in grants together with his team at the FTN. By bringing together electronics and other scientific fields such as medicine or agriculture, they are making everyday life of people easier. One such project is SALSET, dedicated to microfluid devices that are installed in dentures with rinse canals and reservoirs.

“Autistic children can’t develop dental hygiene habits and it is common for this to take a toll on the health of their teeth. Using our microfluid chips, you can wash your teeth wirelessly, using your phone, every, say, six hours, or you can dispense essential oils. By linking electronics with stomatology techniques, we can contribute to better oral health and, therefore, health in general,” says Stojanović and adds that this is exactly what science does: it improves the quality of life.

For example, in five years, STRENTEX project will allow us to buy a shirt that will have EKG-monitoring electrodes embedded, abolishing the need to connect to an external EKG device. Also, we will be able to carry our babies in carriers with embedded humidity, temperature and heartrate sensors. It sounds unbelievable, but there’s more. Project AQUASENSE in which the FTN acts as a partner, is developing detection sensors for water quality. As part of this project, the team at the FTN is working together with a team from Germany to create an underwater robot carrying sensors that detect water pollutants; the little snorkeler should start swimming in a yeah and a half.

Still, we shouldn’t forget about the project methodology. That is why Stojanović wrote and received funding for a project dedicated to responsible research in the Western Balkans. Fostering responsible science and innovation is a project coordinated by the FTN in consortium with another 13 partners from France, Austria, Greece, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Albania. Dedicated to issues within the scientific community, the project aims to develop the methodology of measuring, that is, for instance, improving gender issues, ethics, open science, etc. This is also the only project that doesn’t develop specific products but serves as a basis for other project.

As a coordinator and author of these important projects, Goran Stojanović strives to provide continuous professional training for members of the scientific community in writing competitive projects, because that is the way institutions in Serbia can position them as desirable cooperation partners.

“In practical areas we are engaged in, we cannot rely only on laptops and our brains; we have to also rely on powerful and expensive equipment, which is why EU programmes are so badly needed. You get water at the source. And if there’s an EU Commission programme worth nearly 80 billion euros like HORIZON, we, Serbian scientists must be trained to bring some of that money to Serbia and develop science right here. If we don’t, someone else will take that money. That is how, by investing in our institutions, we get to develop science on our soil,” Stojanović explains.

Horizon 2020 is a framework programme of the European Union for research and innovation, which the Republic of Serbia joined on 1 July 2014. Following the first seven-year budget period, another programme was launched, dubbed Horizon Europe, that will cover the period from 2021 to 2027. The objective of the programme is to support pioneering research projects, support research in the area of global challenges and technological innovation, as well as to ensure Europe’s leading position in the field of research and market creation. The budget set aside for Horizon Europe stands at 95.5 billion euros.